In a 2020 paper titled “The Value of Diversification,” professors Paolo Sodini (currently at the Stockholm School of Economics) and Luis M. Viceira (Harvard Business School) called diversification ” the only ‘free lunch’ available to investors.” They explain:

The idea of diversification is one of the most powerful ideas in Finance, and probably the only “free lunch” available to investors. This Nobel Prize winning idea is behind many of the financial services that help us cope with risk and uncertainty, from car, life, or health insurance to mutual funds, exchanged-traded funds (ETFs), and all kinds of collective investment vehicles.

This idea is rooted in basic statistical science: While independent individual risks can be unpredictable, the frequency with which those risks tend to realize in a large population is largely predictable. We never know if we will be involved in a rear end collision as we get on the road, but the total number of such accidents in a given month in a region is much more predictable. This basic scientific fact opens to the door to one of the most fascinating ideas in finance: Risk sharing, or the idea that we can protect ourselves from the potentially devastating impact of individual risks by pooling them together and sharing their cost with others. This idea is behind one of the most important institutions in modern societies: Insurance.

This idea applies equally well in investing. Any company can experience a significant loss of value as the result of mistakes of its own making, such as designing a flawed new aircraft or folding phone screen, or Fortuna’s making, such as the death of a charismatic corporate leader in a ski accident or a technological discovery that deems a specific product suddenly obsolete. These idiosyncratic events are largely unpredictable, especially to outsiders. Investing all of our savings in one company exposes us to those potentially catastrophic risks.

But the overall frequency of such events is predictably bounded. We can avoid a disastrous idiosyncratic loss by investing in many companies, not just one, just like insurance companies are able to offer car insurance to all of us for a fraction of what it costs to fix a single car by pooling thousands of risks together, because only a few come predictably to fruition in a large population.

Finance goes well beyond translating this very important truth of Statistics into an investing insight. First, Finance notes that we as investors should require compensation for the risks we take. If we have two opportunities to invest, each of which we expect to pay a million krona in a year, we should be willing to pay more for the one whose payoff is more certain. Equivalently, in terms of return (the expected payoff divided by the price we pay), we should require a larger return on the riskier investment to invest in it.

Second, some risks are more diversifiable than others in the sense that their impact can be reduced more through diversification. Independent (or idiosyncratic) risks are more diversifiable than correlated risks. The impact of the loss of value from a failed product launch by a specific company on the value of a well diversified portfolio is trivially small, while the impact of a global recession might not be, because it is a risk that is likely to affect the value of most companies. Nevertheless, unless risks are perfectly correlated, diversification always helps reduce overall portfolio risk. Not all companies will be impacted in the same degree by a global recession.

Third, all investors (“the market”) are willing to hold diversifiable or idiosyncratic risks for very little compensation, while they require compensation for correlated risks. Indeed, the typical stock in the market has a return volatility which is twice the volatility of a well diversified portfolio (“the market portfolio”) but its average return is about the same as the return on the market portfolio. And within asset classes, riskier asset classes (such as equities) tend to have higher average returns than less risky asset classes (such as bonds). Unless one has very good reasons to concentrate one’s savings in very few securities, being undiversified is very costly. It simply increases the risk of significant loss for no obvious upside. In today’s world, we can dramatically reduce investment risk with no penalty in expected return through collective investment vehicles that charge extremely low fees. Diversification is indeed a free lunch.

An investor might find worth to be undiversified if she or he has insights about the future of specific companies, industries, or regions which are clearly superior to those held by every other investor in the market. But that investor should better make sure her or his insights are truly superior because there is another uncomfortable mathematical truth that might come to bite her or him: Active investing is a zero-sum game. One investor’s gain from holding a portfolio different from the market portfolio comes at the expense of another investor’s loss. If we are undiversified, we are either winners or losers. There is no middle ground.

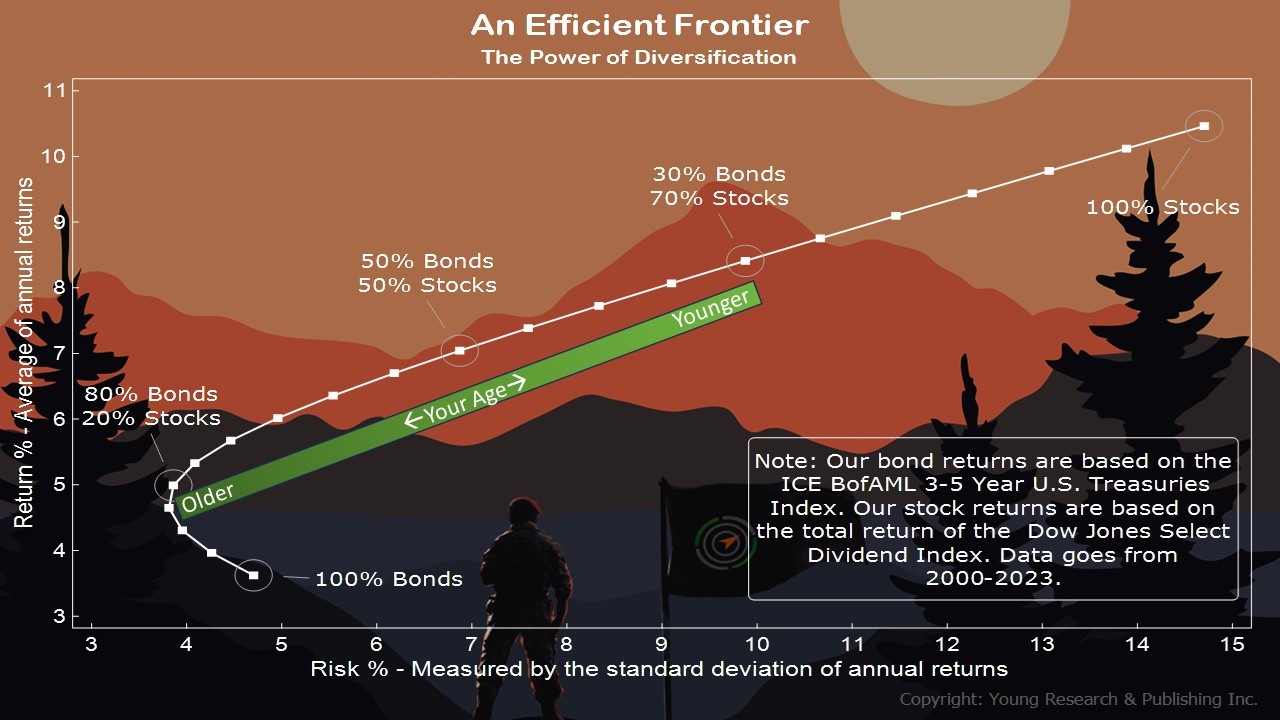

The principles explained by Sodini and Viceira are born out further in the concept of the Efficient Frontier, pioneered by Markowitz, and shown below in my graphic. For some portfolios, diversification can add return and reduce risk. That’s the free lunch.

Originally posted on Your Survival Guy.

One of the more common trends Your Survival Guy sees in investment portfolios is a lack of diversification. Through the years, investors add more money to the winners while the losers are shoved to the side like misfit toys. Over time, portfolios look less like a toy box and more like a mantle of six or seven trophy stocks. That’s dangerous.

If you look at the S&P 500 today, it reminds me of that mantle or trophy case. It looks nice. Who doesn’t like a shiny trophy? But will the winning continue?

Yesterday, in a conversation with my father-in-law Dick Young we talked about diversification. “Survival Guy,” he said. “Greetings from the Key West. As we were discussing the other day, diversification is discipline. Many investors are simply not up to the task. It’s too hard to overcome inertia to make the necessary decisions.”

Later in the day, in a conversation with clients, we talked about the “magnificent seven” in the S&P 500: Seven names make up a third of its value while the other 493 only two-thirds. That’s not a level of diversification I’m comfortable with. Where’s the margin of safety? And it’s not just the S&P 500 Index funds that concern me. Look at the top 10 holdings of a lot of mutual funds or ETFs and you’ll see the same seven names.

It’s the Snow White portfolio with the same seven doing all the work. But for how long?

Portfolio managers are under tremendous pressure to keep pace with the S&P 500 or lose their jobs or their investors. If you consider the makeup of most funds, including the target maturity ones, you’ve got a lot of money in just a few names. But keeping up with the Joneses, or the Dow Jones, for that matter, is what their game is all about. This movie’s not over.

Action Line: If you need help with your trophy case, I’m here.