Daniel Kahneman, one of the founders of behavioral economics, a branch of thought that sees people as they are, impulsive, prone to mistakes, and pushed by their emotions, rather than the fully rational actors of traditional economic thought, has passed away at 90 years old. Kahneman was a psychologist first, and an economist by happenstance. He understood that people’s desire to “do something,” is what could get them into trouble. He said, “All of us would be better investors if we just made fewer decisions.” Sounds like Jack Bogle’s “Don’t just do something, stand there.” Making emotional decisions can be an investment killer.

Kahneman and his partner, Amos Tversky, used experiments to prove that the pain of losing money exceeded the pleasure of making it. In The Wall Street Journal, Jason Zweig, who worked with Kahneman on his book, Think, Fast and Slow (though they didn’t complete the project together), recalls Kahneman’s work on the pain of losses, writing:

I first met Danny, as everyone called him, at a conference on behavioral economics in 1996. For years, as an investing journalist, I had wondered: Why are smart people so stupid about money?

About five minutes into Danny’s presentation, I realized he had the answers—not only to that question, but to nearly every mystery of financial behavior.

Why do we sell our winners too soon and hang onto our losers too long? Why don’t we realize that most hot streaks are just luck? Why do we say we have a high tolerance for risk and then suffer the torments of the damned when the market falls? Why do we ignore the odds when we know they’re stacked against us?

Danny paced softly back and forth at the front of the room, his blue-green eyes sparkling with amusement as he documented these behaviors and demolished conventional economic theory.

For decades, he and Tversky had conducted experiments, almost childlike in their simplicity, to see how people really think and behave.

No, Danny said, money lost isn’t the same as money gained. Losses feel at least twice as painful as gains feel pleasant. He asked the conference attendees: If you’d lose $100 on a coin toss if it came up tails, how much would you have to win on heads before you’d take the bet? Most of us said $200 or more.

No, people don’t incorporate all available information. We think short streaks in a random process enable us to predict what comes next. We think jackpots happen more often than they do, making us overconfident. We think disasters are more common than they are, making us suckers for schemes that purport to protect us.

Ask people if they want to take a risk with an 80% chance of success, and most say yes. Ask instead if they’d incur the same risk with a 20% chance of failure, and many say no.

Noting that the stocks people sell outperform the ones they buy, Danny joked that “the cost of having an idea is 4%.”

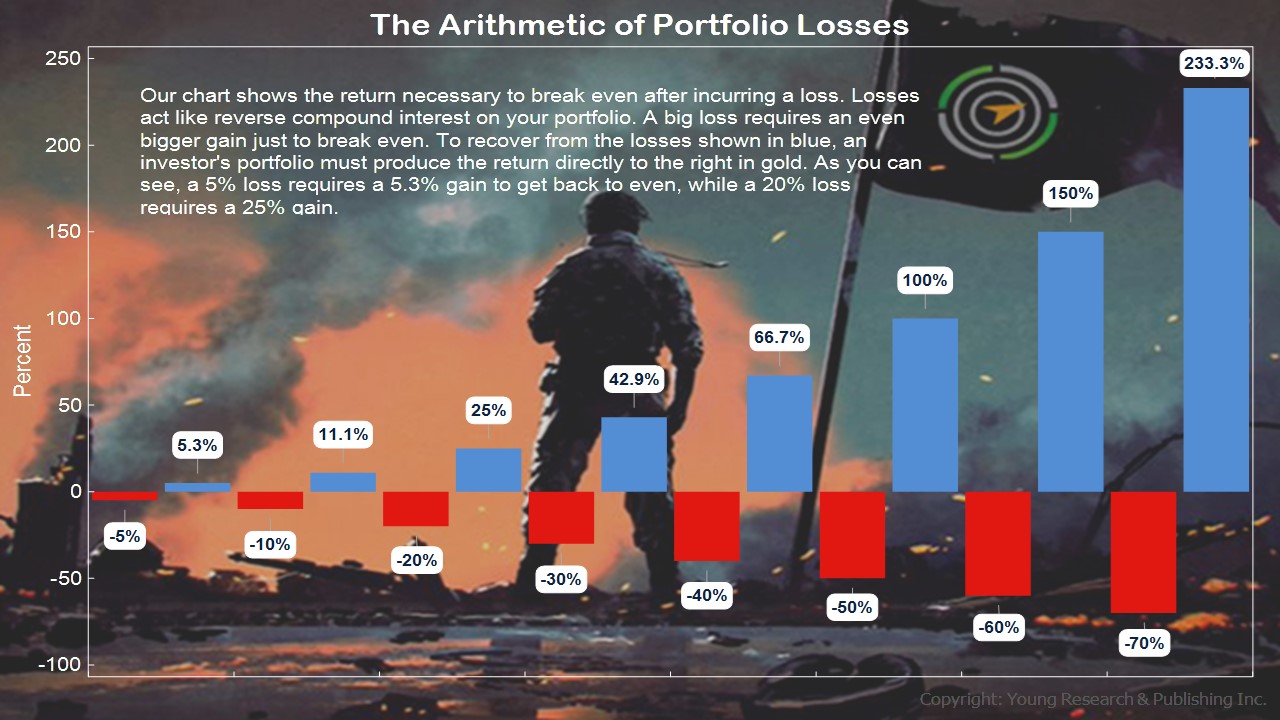

Action Line: Investors realize that making money back is a lot harder than not losing it in the first place. Sometimes though, they forget, and greed beats fear in the emotional balance. The arithmetic of portfolio losses can be a shock to those finding themselves on the losing end. When you want to talk about risk tolerance, the pain of losses, and Thinking Fast and Slow, I’m here. In the meantime, click here to subscribe to my free monthly Survive & Thrive letter.