Most Americans have become accustomed to the idea that when they use Google or Facebook, information on their Internet habits is being sold to advertisers who want to target them with ads. But until now that phenomenon has been mostly confined to cyberspace, and there are ways to avoid them.

That’s all beginning to change though. Now industries that were around even before the Internet are attempting to make profits from your private information. The most dangerous of these is your bank.

The Associated Press has reported that banks are selling information on customers’ spending habits to advertisers. Many of the customers don’t even know this is happening. Anick Jesdanun reports:

Suppose you were to treat yourself to lunch on Cyber Monday, the busiest online shopping day of the year. If you order ahead at Chipotle — paying, of course, with your credit card — you might soon find your bank dangling 10% off lunch at Little Caesars. The bank would earn fees from the pizza joint, both for showing the offer and processing the payment.

Wells Fargo began customizing retail offers for individual customers on Nov. 21, joining Chase, Bank of America, PNC, SunTrust and a slew of smaller banks.

Unlike Google or Facebook, which try to infer what you’re interested in buying based on your searches, web visits or likes, “banks have the secret weapon in that they actually know what we spend money on,” said Silvio Tavares of the trade group CardLinx Association, whose members help broker purchase-related offers. “It’s a better predictor of what we’re going to spend on.”

While banks say they’re moving cautiously and being mindful of privacy concerns, it’s not clear that consumers are fully aware of what their banks are up to.

Banks know many of our deepest, darkest secrets — that series of bills paid at a cancer clinic, for instance, or that big strip-club tab that you thought stayed in Vegas. A bank might suspect someone’s adulterous affair long before the betrayed partner would.

“Ten years ago, your bank was like your psychiatrist or your minister — your bank kept secrets,” said Ed Mierzwinski, a consumer advocate at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group. Now, he says, “they think they are the same as a department store or an online merchant.”

Have you considered that your bank may be selling your private spending information? If you’re like most Americans, that answer is probably no. But they are.

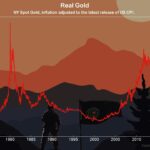

A growing number of people in countries around the world are utilizing safety deposit boxes and home safes in order to protect their cash. With banks offering so little in the way of interest on savings (sometimes even charging on deposits) and facing the prospect of having their personal information sold to the highest bidder, it’s no surprise people are choosing alternative means of storage for their money.

E.J. Smith - Your Survival Guy

Latest posts by E.J. Smith - Your Survival Guy (see all)

- “What Do You Do If the Market Crashes?” - April 19, 2024

- Costco Gold Bars Sell Out Despite Premium Price - April 19, 2024

- A Wise Man’s Take on the Boston Bruins Playoff Chances - April 19, 2024

- Is Your Retirement Life a Mess? Let’s Talk - April 18, 2024

- Your Survival Guy Learns from Marie Kondo - April 18, 2024