Don’t be head-faked by the Federal Reserve’s 25bps cut in the Fed Funds Rate (FFR) this week.

Because the real story is in Repo where demand for Treasuries has been through the roof.

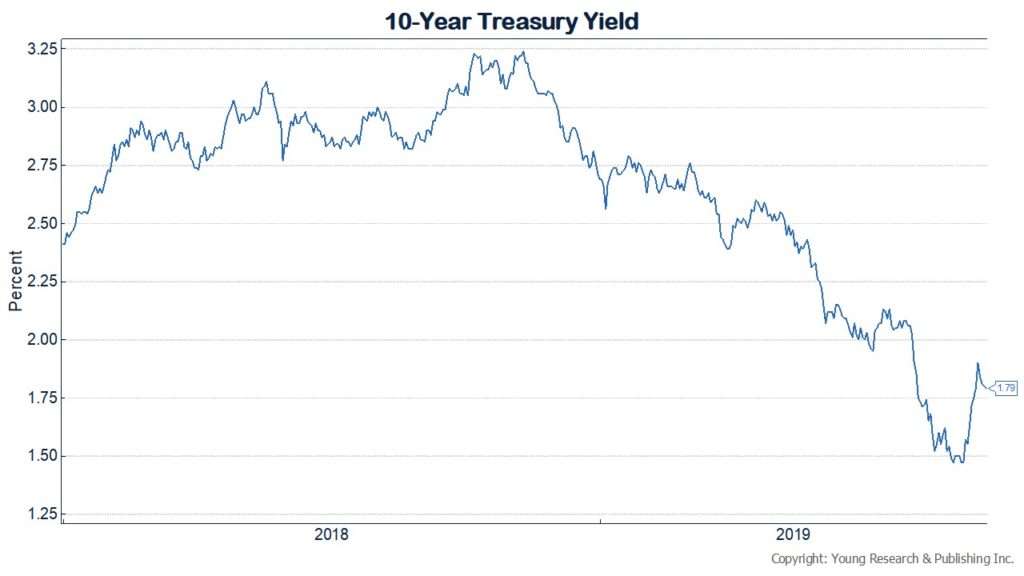

If you look at my chart on the 10-year Treasury you can see this problem began not in 2019 but at the end of May 2018.

Most investors, including the Fed, don’t understand bonds. The bond market, like stocks, is ruled by supply and demand just like real estate, for example.

Something is going on with the plumbing of the global monetary system that the Fed is clueless about.

For more read this from Jeffrey Snider:

What it means as a floor is financial firms are given another set of options. In this case, T-bills are a money alternative to RRP. As such, there should never be an instance where they would yield less. Why would any firm choose to lend money to the US government by buying a T-bill at 1.99% when they can “lend” to the Federal Reserve also collateralized by a US government security (that’s what reverse repo means) at 2%? The spread may be small, but it is the market saying there is serious demand for the bills, so much it is willing to take a little less in profit to hold them.

This is not the first time we’ve seen this, either. In fact, you can go back to the early months of 2017 long before EFF, IOER, and Trump’s-tax-reform-is-to-blame and you will see many days and weeks of the same thing – bill rates dropping below the RRP “floor.” The most egregious was June 23, 2017, when the 4-week rate priced a stunning 24 bps underneath.

What that said in early 2017 was that there was a collateral shortage. Yep, repo is the reason for heightened demand for securities compared to the Fed’s money alternatives. An ongoing one, yes, since in many ways this remains the big problem leftover from the 2008 crisis. But in the specific context of 2017 and that reflationary period, those bill rates showed the shortage had become more acute.

But if that was so, and it was, why didn’t it derail everything back then? This is again where we leave evidence and fall into interpretation (only to come back to evidence again in 2019). What was likely to have happened was the global eurodollar banking system responded to the shortage of Treasuries in 2017 by manufacturing collateral.

It was “globally synchronized growth”, after all, and many really believed that worldwide recovery was at hand. Therefore, much, much lower risks because meaningful economic growth reduces the chances of something serious going wrong. On that premise, it isn’t hard to imagine at least some global banks plunging back into the world of securities lending betting on the positive economic scenario.

You want to speculate on junk corporates issued by some company in Brazil? You can’t go to the repo market to fund that position because the repo market won’t take it. But you might be able to go to one of these more optimistic dealer banks and “borrow” some Treasuries putting up your junk as collateral for the transformation. The more willing the dealers, the more this goes on (and the cheaper it gets).

It’s the same sort of thing AIG did in the precrisis era which eventually led to its bailout (it wasn’t credit default swaps which nearly brought the company down, it was securities lending of just this type). In other words, banks engaging in these transactions know what the true downside looks like. They must not have believed there was much downside given, again, “globally synchronized growth.”

But what if that proved to be nothing more than a bumper sticker slogan? Now you begin to see the early months of 2018 very differently. If you are a dealer bank who had been involved in especially Eurobond tranformations throughout 2017 as a bypass of the Treasury shortage, then you scale back if not stop the transformations and bring the system back to…the Treasury shortage.

Read more here.