Homeless camp on a sidewalk in downtown Los Angeles, makeshift shelters made from tents and blankets. By Simone Hogan @ Shutterstock.com

In the Orange County Register, veteran California journalist and political analyst Dan Walters, examines the hard choice facing city officials in Sacramento, and state officials in California. The problem both governments have is their pensions.

Despite problems with its pensions, Sacramento officials are already thinking up ways to spend money they haven’t received from future taxes on things like “infrastructure, affordable housing, cultural amenities and incentives to attract new business,” while ignoring the massive hole in the city’s retirement funding. Walters writes:

As they pore over proposals to spend Measure U money, however, Steinberg, et al, try to avoid the financial gorilla that is prowling city hall – rapidly rising costs of pensions for city employees that threaten to soak up all the money.

The city’s current budget declares that over the next five years, mandatory payments to the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) will increase by 58 percent or $47.3 million a year – almost exactly what the extra half-cent of sales tax in Measure U would raise.

Most of that money is directed at reducing the immense unfunded liabilities that CalPERS acquired during the Great Recession a decade ago and has not been able to erase despite an extended period of economic prosperity. Recently, CalPERS reported that its earnings during the preceding year fell a bit short of expectations, which means its unfunded liabilities grew even more.

Eventually, to meet its ever-increasing pension payments, Sacramento will either have to use Measure U’s revenues, thus setting aside the ambitious civic improvements Steinberg and others want to make, or cut other city services. It’s simple, inescapable arithmetic.

Sacramento certainly isn’t alone. Throughout California, as pension payments accelerate faster than property and sales tax revenue, city officials are facing similar tradeoffs and/or asking their voters to raise taxes.

A new study by UC-Berkeley Professor Sarah Anzia, using data from a variety of sources, sees it as a nationwide problem. “My analysis here,” Anzia writes, “shows that as local governments spend more on pensions, they have fewer public-sector jobs to offer – an implication that is not positive for government employees or their unions.”

Anzia foresees a “pension-induced transformation of local government” and suggests that “the future of local government may look very different than the past” as a result.

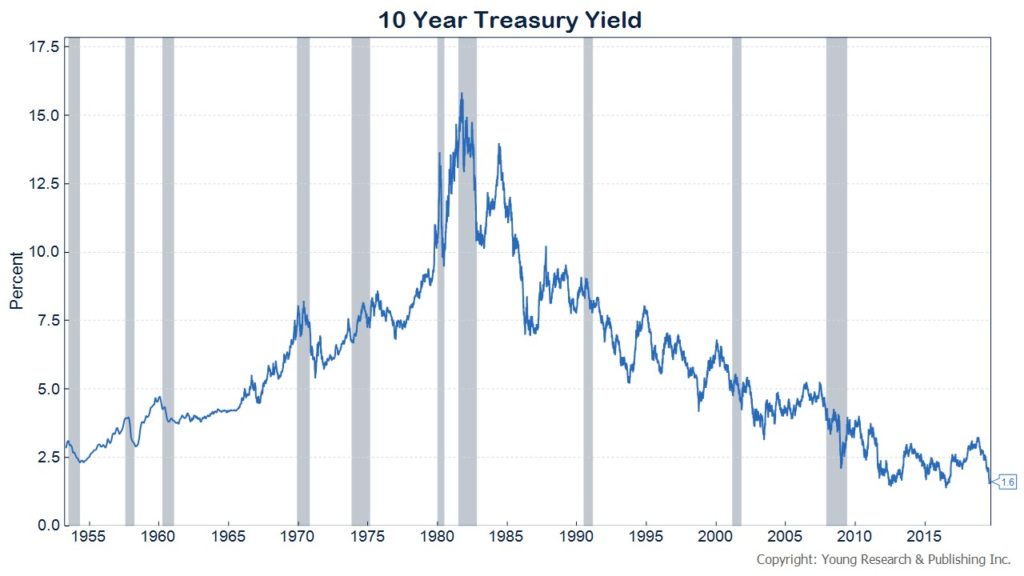

Public pension funds are in trouble around the country. Much of the cause of the pension problem is rooted in unrealistic return expectations. Pensions are typically balanced funds, with averaged assumed rates of return of 7.5%. A typical fund will invest about a third of its assets in fixed income. Those return expectations are unrealistic today with yields in the bond market are extremely low. For example, the 10-year treasury rate is near an all-time low (see chart below).

As Walters indicates, when municipalities believe their pension funds will earn unrealistically high returns, they spend money they should have saved on other priorities. With that money gone, administrators are forced to come back later, hat in hand, looking for more revenue. The phenomenon is not isolated to California. I’ve been noting bad pension behavior all around the country for years. Here’s a sample of the carnage:

- Illinois: New Governor, Same Old Pension Pyramid Scheme

- American Municipalities Offer Less Info, More Debt

- Is Your State’s Pension System about to Collapse?

- New Michigan Law Reveals Big Trouble

- Fuzzy Math Can’t Hide This State’s Pension Trouble Anymore

If you’re living in a state or city (or both) with a vastly underfunded pension, you can expect to be asked to pay more in taxes, later on, to make up for the lack of proper pension saving today.

E.J. Smith - Your Survival Guy

Latest posts by E.J. Smith - Your Survival Guy (see all)

- “What Do You Do If the Market Crashes?” - April 19, 2024

- Costco Gold Bars Sell Out Despite Premium Price - April 19, 2024

- A Wise Man’s Take on the Boston Bruins Playoff Chances - April 19, 2024

- Is Your Retirement Life a Mess? Let’s Talk - April 18, 2024

- Your Survival Guy Learns from Marie Kondo - April 18, 2024