In my conversations with you, you’re telling me home prices are crazy. It really doesn’t matter where you live. Take, for example, a realtor and prospective client I was talking with yesterday. He operates in the mountain west and said he has tons of buyers, just no homes to sell. No supply. And that’s residential real estate today in a nutshell—supply.

In my conversations with you, you’re telling me home prices are crazy. It really doesn’t matter where you live. Take, for example, a realtor and prospective client I was talking with yesterday. He operates in the mountain west and said he has tons of buyers, just no homes to sell. No supply. And that’s residential real estate today in a nutshell—supply.

On a recent trip to Key West, we talked with a realtor getting ready to show a house as we were walking by. Curious, we asked if we could take a quick look. This tastefully done home was a perfect, cozy, old town Key West conch retreat. The only problem? Meet the neighbors. They surround the house on all three sides. Not uncommon for KW, but this puts new meaning to the word postage stamp lot.

The property line on one side is basically the side of one neighbor’s house. On the other, a big two-story manse in need of major renovations lurks high above the not-so-private plunge pool. And along the back another house. No matter. It sold the next week for $1.4 million—apparently a bit underpriced. Wow.

And that’s the story across much of the country. It’s a supply issue. If you want to live in The Point section of Newport, RI, where we bought our first home, you need to pay the entry fee. They’re not making any more neighborhoods like it, where you’re close to the water and restaurants. The market is the market, but markets don’t always go up.

Your Survival Guy’s interest perked up recently, reading a feature in the WSJ on the glut of harvestable trees in the South and that there aren’t enough sawmills to handle the demand for lumber. Apparently, there’s not that many sawmills in America. According to IBISWorld, there are only 2,975 businesses in America in the sawmilling and wood production industry, employing only about 82,000 people. Compare that to farming which employs 2.6 million Americans, and you begin to see just how small the wood production industry is. No wonder prices are way up.

The WSJ reports on the glut of logs waiting for sawmill supply. Ryan Dezember and Vipal Monga write:

Timber growers across the U.S. South, where much of the nation’s logs are harvested, have gained nothing from the run-up in prices for finished lumber. It is the region’s sawmills, including many that have been bought up by Canadian firms, that are harvesting the profits.

Sawmills are running as close to capacity as pandemic precautions will allow and are unable to keep up with lumber demand. The problem for timber growers is that so many trees have been planted between the Carolinas and Texas that mills are paying the lowest prices in decades for logs.

The log-lumber divergence has been painful for thousands of Southerners who are counting on pine trees for income and as a way to hold on to family land. And it has been incredibly profitable for forest-products companies that have been buying mills in the South. Three Canadian firms— Canfor Corp. CFPZF 1.63% , Interfor Corp. IFP 3.11% and West Fraser Timber Co. WFG 5.18% —control about one-third of the South’s lumber-making capacity. Since bottoming out last March, shares of the Canadian sawyers have risen more than 300%, compared with a 75% climb of the S&P 500 index.

The surplus of standing pine is such that growers, foresters and mill executives expect that even with mills sawing at capacity and new facilities coming online, it could be another decade, maybe two, before enough trees are felled to balance supply with demand.

Meanwhile, it’s a buyer’s market for logs down South, said Don Kayne, Canfor’s chief executive.

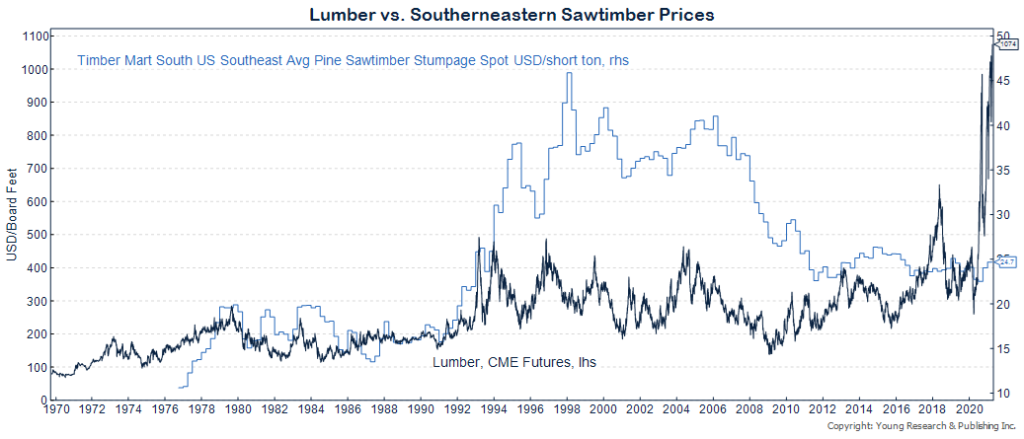

You can see the divergence in lumber and timber prices in the chart below. Timber price peaked in 1998, while prices for lumber are hitting new highs daily.

Action Line: With too much money chasing too few goods, and tons of money supplied by the Fed to add to the mix, beware of supply. There’s a lot of levers involved today, not just a scarcity of properties. What could possibly go wrong?

E.J. Smith - Your Survival Guy

Latest posts by E.J. Smith - Your Survival Guy (see all)

- Rule #1: Don’t Lose Money - April 26, 2024

- How Investing in AI Speaks Volumes about You - April 26, 2024

- Microsoft Earnings Jump on AI - April 26, 2024

- Your Survival Guy Breaks Down Boxes, Do You? - April 25, 2024

- Oracle’s Vision for the Future—Larry Ellison Keynote - April 25, 2024