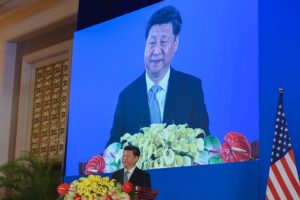

Chinese President Xi Jinping addresses U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, Chinese Vice Premier Liu Yandong, Chinese Vice Premier Wang Yang, and Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi, and other U.S. and Chinese officials on June 6, 2016, in a villa at the Diaoyutai Guest House complex in Beijing, China, as the Chinese leader opens a two-day Strategic and Economic Dialogue between their respective countries. [State Department photo/ Public Domain]

Xi Jinping, the ruler of China, suffers from several internal inconsistencies which greatly reduce the cohesion and effectiveness of his leadership. There is a conflict between his beliefs and his actions and between his public declarations of wanting to make China a superpower and his behavior as a domestic ruler. These internal contradictions have revealed themselves in the context of the growing conflict between the U.S. and China.

At the heart of this conflict is the reality that the two nations represent systems of governance that are diametrically opposed. The U.S. stands for a democratic, open society in which the role of the government is to protect the freedom of the individual. Mr. Xi believes Mao Zedong invented a superior form of organization, which he is carrying on: a totalitarian closed society in which the individual is subordinated to the one-party state. It is superior, in this view, because it is more disciplined, stronger and therefore bound to prevail in a contest.

Relations between China and the U.S. are rapidly deteriorating and may lead to war. Mr. Xi has made clear that he intends to take possession of Taiwan within the next decade, and he is increasing China’s military capacity accordingly.

He also faces an important domestic hurdle in 2022, when he intends to break the established system of succession to remain president for life. He feels that he needs at least another decade to concentrate the power of the one-party state and its military in his own hands. He knows that his plan has many enemies, and he wants to make sure they won’t have the ability to resist him.

It is against this background that the current turmoil in the financial markets is unfolding, catching many people unaware and leaving them confused. The confusion has compounded the turmoil.

Although I am no longer engaged in the financial markets, I used to be an active participant. I have also been actively engaged in China since 1984, when I introduced Communist Party reformers in China to their counterparts in my native Hungary. They learned a lot from each other, and I followed up by setting up foundations in both countries. That was the beginning of my career in what I call political philanthropy. My foundation in China was unique in being granted near-total independence. I closed it in 1989, after I learned it had come under the control of the Chinese government and just before the Tiananmen Square massacre. I resumed my active involvement in China in 2013 when Mr. Xi became the ruler, but this time as an outspoken opponent of what has since become a totalitarian regime.

I consider Mr. Xi the most dangerous enemy of open societies in the world. The Chinese people as a whole are among his victims, but domestic political opponents and religious and ethnic minorities suffer from his persecution much more. I find it particularly disturbing that so many Chinese people seem to find his social-credit surveillance system not only tolerable but attractive. It provides them social services free of charge and tells them how to stay out of trouble by not saying anything critical of Mr. Xi or his regime. If he could perfect the social-credit system and assure a steadily rising standard of living, his regime would become much more secure. But he is bound to run into difficulties on both counts.

To understand why, some historical background is necessary. Mr. Xi came to power in 2013, but he was the beneficiary of the bold reform agenda of his predecessor Deng Xiaoping, who had a very different concept of China’s place in the world. Deng realized that the West was much more developed and China had much to learn from it. Far from being diametrically opposed to the Western-dominated global system, Deng wanted China to rise within it. His approach worked wonders. China was accepted as a member of the World Trade Organization in 2001 with the privileges that come with the status of a less-developed country. China embarked on a period of unprecedented growth. It even dealt with the global financial crisis of 2007-08 better than the developed world.

Mr. Xi failed to understand how Deng achieved his success. He took it as a given and exploited it, but he harbored an intense personal resentment against Deng. He held Deng Xiaoping responsible for not honoring his father, Xi Zhongxun, and for removing the elder Xi from the Politburo in 1962. As a result, Xi Jinping grew up in the countryside in very difficult circumstances. He didn’t receive a proper education, never went abroad, and never learned a foreign language.

Xi Jinping devoted his life to undoing Deng’s influence on the development of China. His personal animosity toward Deng has played a large part in this, but other factors are equally important. He is intensely nationalistic and he wants China to become the dominant power in the world. He is also convinced that the Chinese Communist Party needs to be a Leninist party, willing to use its political and military power to impose its will. Xi Jinping strongly felt this was necessary to ensure that the Chinese Communist Party will be strong enough to impose the sacrifices needed to achieve his goal.

Mr. Xi realized that he needs to remain the undisputed ruler to accomplish what he considers his life’s mission. He doesn’t know how the financial markets operate, but he has a clear idea of what he has to do in 2022 to stay in power. He intends to overstep the term limits established by Deng, which governed the succession of Mr. Xi’s two predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin. Because many of the political class and business elite are liable to oppose Mr. Xi, he must prevent them from uniting against him. Thus, his first task is to bring to heel anyone who is rich enough to exercise independent power.

That process has been unfolding in the past year and reached a crescendo in recent weeks. It started with the sudden cancellation of a new issue by Alibaba’s Ant Group in November 2020 and the temporary disappearance of its former executive chairman, Jack Ma. Then came the disciplinary measures taken against Didi Chuxing after it floated an issue in New York in June 2021. It culminated with the banishment of three U.S.-financed tutoring companies, which had a much greater effect on international markets than Mr. Xi expected. Chinese financial authorities have tried to reassure markets but with little success.

Mr. Xi is engaged in a systematic campaign to remove or neutralize people who have amassed a fortune. His latest victim is Sun Dawu, a billionaire pig farmer. Mr. Sun has been sentenced to 18 years in prison and persuaded to “donate” the bulk of his wealth to charity.

This campaign threatens to destroy the geese that lay the golden eggs. Mr. Xi is determined to bring the creators of wealth under the control of the one-party state. He has reintroduced a dual-management structure into large privately owned companies that had largely lapsed during the reform era of Deng. Now private and state-owned companies are being run not only by their management but also a party representative who ranks higher than the company president. This creates a perverse incentive not to innovate but to await instructions from higher authorities.

China’s largest, highly leveraged real-estate company, Evergrande, has recently run into difficulties servicing its debt. The real-estate market, which has been a driver of the economic recovery, is in disarray. The authorities have always been flexible enough to deal with any crisis, but they are losing their flexibility. To illustrate, a state-owned company produced a Covid-19 vaccine, Sinopharm, which has been widely exported all over the world, but its performance is inferior to all other widely marketed vaccines. Sinopharm won’t win any friends for China.

To prevail in 2022, Mr. Xi has turned himself into a dictator. Instead of allowing the party to tell him what policies to adopt, he dictates the policies he wants it to follow. State media is now broadcasting a stunning scene in which Mr. Xi leads the Standing Committee of the Politburo in slavishly repeating after him an oath of loyalty to the party and to him personally. This must be a humiliating experience, and it is liable to turn against Mr. Xi even those who had previously accepted him.

In other words, he has turned them into his own yes-men, abolishing the legacy of Deng’s consensual rule. With Mr. Xi there is little room for checks and balances. He will find it difficult to adjust his policies to a changing reality, because he rules by intimidation. His underlings are afraid to tell him how reality has changed for fear of triggering his anger. This dynamic endangers the future of China’s one-party state.

A condemnation of political manipulation is rich coming from Soros, but that he would take to the public sphere to denounce Xi is an indication of just how afraid Soros is of the Chinese leader and the Communist Party’s increasing power. The Party’s increasingly confrontational and aggressive manner is causing problems for the rest of the world where the rule of law and openness usually presides.

China’s unpredictable totalitarian behavior has most recently struck at the country’s junk bond market. Serena Ng reports:

The latest Chinese market to buckle under pressure from Beijing’s wide-ranging corporate crackdown: junk bonds.

Companies from China make up the bulk of Asia’s roughly $300 billion high-yield dollar bond market, thanks to a surge in borrowing by the country’s heavily indebted property developers. But the investor optimism that drove that borrowing has collapsed.

Stress has been building following a string of debt defaults and growing concern about a few large issuers, including property giant China Evergrande Group. Sharp price declines in its bonds and those of a few other large Chinese companies, plus concerns about tighter regulation aimed at reining in speculation and soaring housing prices, have pushed the market over the edge.

“There’s a confidence crisis in Chinese high-yield debt,” said Paul Lukaszewski, head of corporate debt for the Asia Pacific region at Aberdeen Standard Investments in Singapore.

The average yield of non-investment-grade U.S. dollar bonds from companies in China topped 14% in late July and early August, around 10 percentage points above the average yield of junk bonds issued by American companies, according to ICE BofA Indices.

The gap between the two recently hit its widest level in a decade, showing how far prices of Chinese bonds have fallen relative to their Western counterparts. Bond yields rise when prices fall.

Many American debt issuers have benefited this year from the Federal Reserve’s easy monetary policy, which has kept interest rates low to spur growth as the U.S. economy rebounds from the coronavirus pandemic. China’s economy, in contrast, returned to expansionary mode last year, and Beijing has resumed a campaign to reduce debt levels in sectors such as real estate, which has put many developers in a tight spot.

The widening regulatory crackdown that sparked a big selloff last month in the shares of internet-technology and education companies has also weighed on Chinese credit markets, pushing down prices of even investment-grade bonds. The moves show China is getting more serious about reining in companies whose business practices are seen at odds with national priorities. Investors are now actively looking for sectors that might be next in the crosshairs.

“A lot of the tension is focused on the property sector, and it’s really been driven by [China’s] policy,” said Sheldon Chan, an Asia credit portfolio manager at T. Rowe Price in Hong Kong.

Action Line: The Chinese market is controlled from the top down. The outcome of any investment you make in it will be controlled by the whims of Xi Jinping and the Communist Party of China. Just like billionaires pushing their own EGOs, with the Communist Party, you invest, and they win.